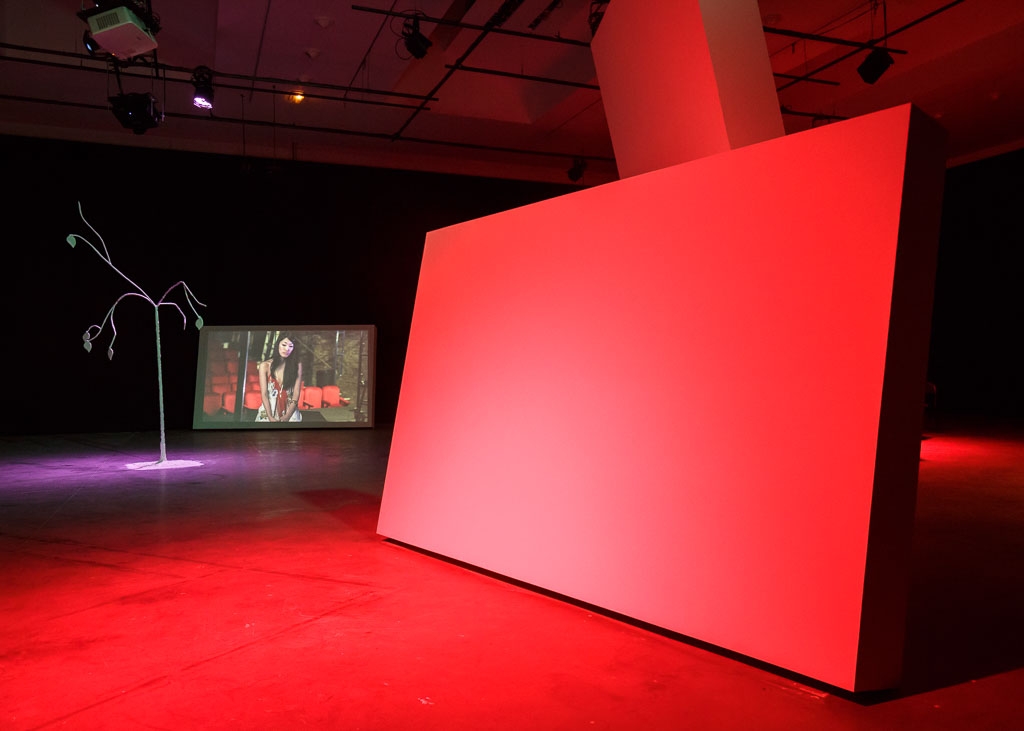

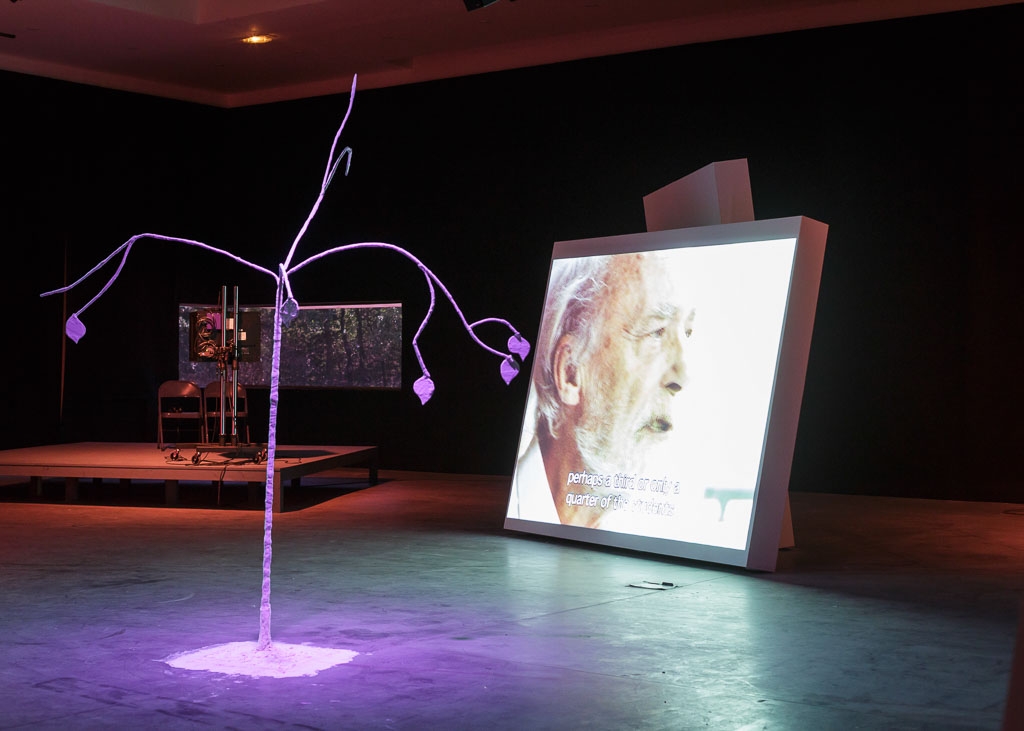

Gerard Byrne, extrait "A thing is a hole in a thing it is not", 2010.

Courtesy of Lisson Gallery, London ; Nordenhake Gallery, Stockholm ; and Green on Red Gallery, Dublin

The FRAC des Pays de la Loire French regional art fund will play host to Gerard Byrne’s first solo exhibition in France, A late evening in the future, from July 5 to September 21, 2014.

In this exhibition – somewhere between installation and retrospective – the Irish artist brings to Carquefou a large number of major works produced over the last ten years.

Boulevard Ampère

44470 Carquefou

France

Free entrance

exhibition opening hours :

wednesday to sunday from 2 to 6 p.m.

In the frame of Songe d’une nuit d’été (Midsummer night’s dream) a contemporary art & heritage trail in the loire valley - from march to november 2014

Gerard Byrne has spent his career revisiting our cultural history: his carefully-documented film productions show public figures of the twentieth century – artists, writers, businessmen – discussing social and political issues of their day. Byrne looks to the media world of his youth (whether publications, television or advertising) for the raw material of his dialogues and conversations. As such, 1984 and Beyond (2005-07) refers to 1960s’ America and its vision of the future, through a discussion organized by Playboy in 1963, and which brings together some of the leading figures in science fiction such as Isaac Asimov and Ray Bradbury. In the midst of these turbulent times, this butch band foresees with complete confidence the end of communism, intergalactic space travel, a society of plenty and complete sexual freedom. Evoking a future yet to happen from a bygone age, the scene is as fascinating as it is disturbing.

Byrne’s twentieth century is full of men, and these men speak mainly about art and sex (women), between revolutionary aspirations and moral conservatism. A thing is a hole in a thing it is not calls upon, through some chequered episodes in its history, some of the major players of Minimalism and the American modern art scene: Robert Morris, Tony Smith, Franck Stella discover, discuss and implement a new vision of the artwork, a pure spatial object. In A Man and a Woman make love (2012), a group of phallocentric surrealists – including André Breton and Raymond Queneau – descant learnedly on pleasure and the mysteries of the female orgasm. Staged on a sitcom set very much in the style of the Belle Epoque, this dialogue published in 1928 in La Révolution surréaliste (The Surrealist Revolution) appears all the more shocking. Between these two issues we glimpse the question of objectivity of forms and of the subjugation of women and nations, a common desire for control, and a form of complicity, which leave their mark on our cultural history.

Deliberately theatrical, Gerard Byrne’s films constantly blur the boundaries between document and fiction, between History and histories. At the FRAC Pays de la Loire, the artist has chosen to bring them back into play in a setting that draws as much on the language of minimalist sculpture and romantic ruin as on the theatre stage. The large gallery, immersed in shadow, is dotted with monumental slabs propped up against one another and with viewing devices. The slabs and screens come alive and switch off; the films are fragmented according to the switching whims of the software controlling the whole installation, and the movements of roaming visitors. Somewhere within the gallery space stands enthroned the reconstruction of the white tree created by Giacometti for a set of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Also borrowed from Beckett is the exhibition’s title: A late evening in the future is the first stage direction in Krapp’s Last Tape, which sees Krapp, a failed writer reduced to vagrancy, soliloquize while listening once again to an old tape spool, a kind of record of “blessed, blissful days” cut short by a distressing break-up. Like the example of Beckett’s set, Gerard Byrne’s exhibition seeks to be an enigmatic twilight zone devoted to recollection, subject to a random and discretionary order. It is therefore for the roaming visitor to reconstruct meaning out of the modernist narratives cleverly deconstructed by the artist.

Julien Zerbone